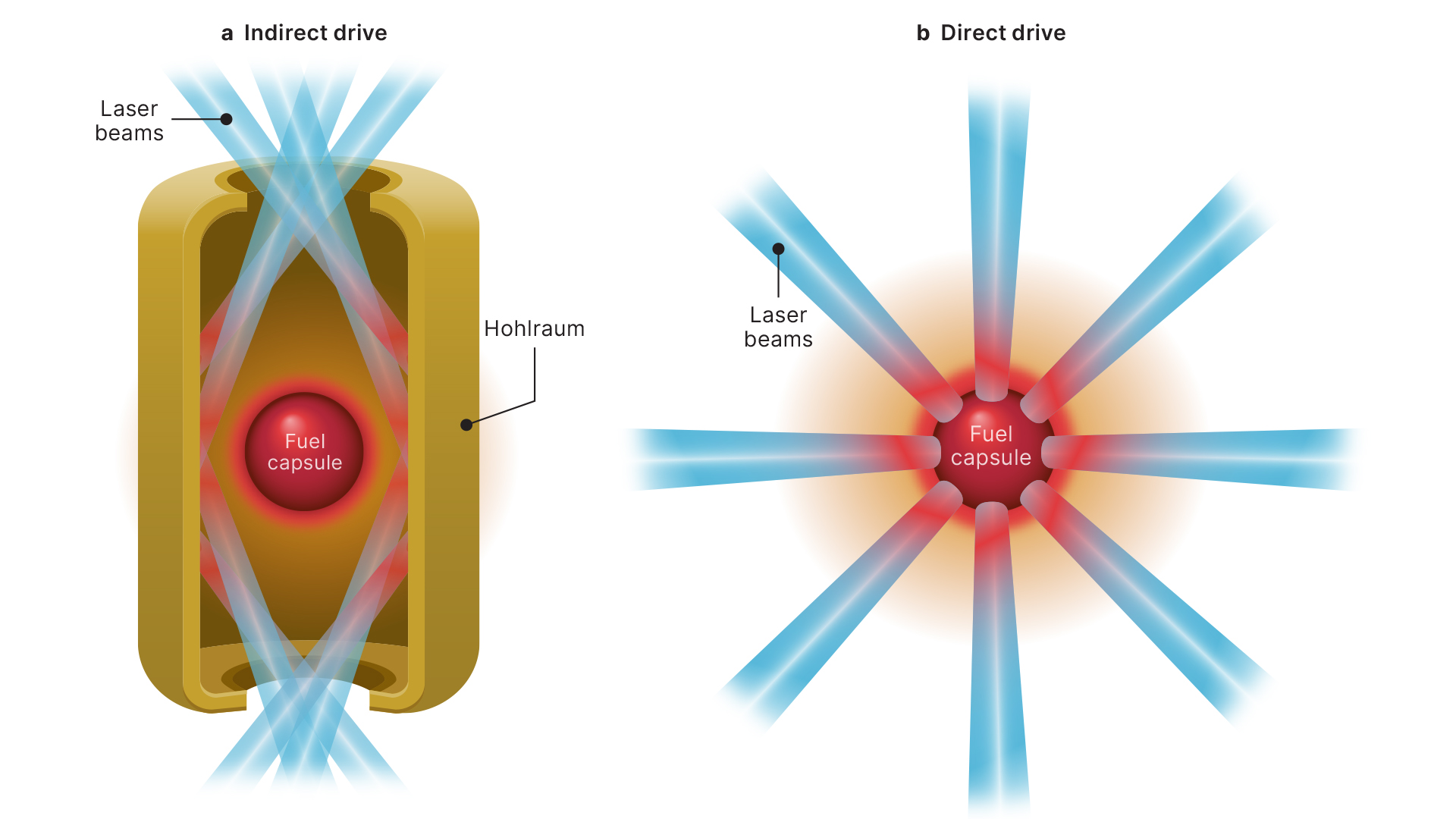

The achievement of ignition in a laboratory setting has renewed interest in defining the requirements for a future high-gain inertial confinement fusion (ICF) facility. Current ignition experiments rely on an indirect-drive method, where laser energy is first converted to a bath of x rays by irradiating the inside of a gold can (called a hohlraum) surrounding the target [Fig. 1(a)]. Direct-drive ICF, on the other hand, offers a promising alternative pathway to ignition at significantly lower laser energies compared to indirect drive. In direct-drive fusion, lasers directly irradiate the fusion target, coupling almost all the energy to the fuel capsule [Fig. 1(b)]. This method is more efficient than indirect drive, where much of the energy is lost in the process of converting laser energy to x rays. We must, however, first overcome two major degradations to direct-drive performance: imprint and laser–plasma instabilities (LPIs). Imprint occurs when spike-like structures in the laser beams (laser speckles) create unwanted 3D nonuniformities on the target surface that seed hydrodynamic instabilities. LPIs are caused when the laser passes through blow-off material and interacts with plasma waves. These waves can scatter laser light away from the target, reducing laser coupling as well as accelerating a small number of electrons to energies high enough to penetrate deep into the target, preheating it and making it harder to compress. New laser technology that increases laser bandwidth (the range of wavelengths of the laser light) offers a solution to both these issues. Increased bandwidth suppresses LPIs and could allow for more-effective smoothing of imprint. With the advent of this next-generation laser technology, now is the time to begin to consider the target requirements for ignition and therefore the design constraints of a direct-drive ignition-capable facility.

Balancing Performance and Stability in ICF Designs

The ICF community relies heavily on radiation-hydrodynamics codes to guide the design process and make inferences about implosion degradation mechanisms. Currently, existing codes do not reproduce previous experiments with sufficient accuracy to reliably predict implosion performance across a wide parameter space. Accordingly, various strategies have been adopted to combine simulation predictions with experimental data and expert knowledge to predict implosion performance.

The majority of ICF implosion designs are performed using 1D simulations that do not account for the impact of 3D fluid instabilities. When using 1D simulations to design implosions, there are a number of tradeoffs that exist between improving 1D performance and increasing susceptibility to fluid instabilities. For example, reducing the adiabat (a measure of the fuel entropy), enhances compression and yield in 1D but increases a target’s susceptibility to a fluid instability called Rayleigh–Taylor (RT) growth. Similarly, reducing the laser spot size increases the amount of laser energy absorbed by the target but at the cost of laser drive uniformity. A target’s susceptibility to laser spot size is often characterized by the ratio of the beam radius to the target radius (Rb/Rt). Additionally, to ignite targets at hundreds of kilojoules of laser energy, it is necessary to use focal-spot zooming, which reduces the laser spot size during convergence. Focal-spot zooming will exacerbate the issue with small laser spots.

In the past, significant increases in target performance have been achieved using a statistical model that combines simulations with experiments to make reliable predictions within a well-understood parameter space [1]. Predicting the performance of a future facility, however, requires us to extrapolate beyond the conditions that are well understood. Extrapolating any such model is inherently risky because it requires physics to scale in a predictable way, which has historically not been the case for ICF. Therefore, ensuring extrapolations are carried out using a strong physics-based approach is the best way to predict the performance of future facilities

Designing ICF implosions involves finding the best set of input parameters to maximize performance. These parameters, such as target dimensions, laser pulse shape, and spot size, provide us with optimum values of measurable quantities—for example, neutron yield. The optimization process must also account for engineering constraints, such as limits on laser intensity to avoid damaging the optics. To make this complex process manageable, scientists use simulation results in place of experimental measurements—for example, they use simpler 1D simulations to predict the fusion yield from an experiment. A major advantage to using simulations is that they can be run thousands of times in a few hours, whereas experiments may only be able to field a handful of targets in an entire day. On the other hand, since 1D simulations cannot fully capture real-world physics, additional adjustments are necessary to ensure accuracy. For example, both of the design approaches that we subsequently discuss in this article (the stability constraints approach and surrogate approach) use the predictions from 1D simulations, which means that additional design constraints are required to account for any damaging effects, such as 3D fluid instabilities. Therefore, the overall design process involves three steps:

- Use experimental data and advanced 2D/3D simulations to define a simplified optimization problem using 1D simulations as a substitute.

- Use 1D simulations to find optimal implosion designs within the corresponding design constraints.

- Validate the designs with more-detailed 2D or 3D simulations.

The two approaches discussed differ mainly in how they account for 3D effects during the approximation process. Even with the computational efficiency of 1D simulations, researchers often settle for a good local optimum rather than a global one, depending on the complexities of the problems at hand.

Stability Constraints Approach

In this approach, we use simple physics arguments to understand the performance of targets without considering complex 3D effects. From there, we restrict design options by setting stability limits based on current experiments. The two main stability factors are:

-

Resistance to RT instability, which is constrained by the empirically derived stability parameter Iα = 6α1.1/IFAR > 1, where α is the adiabat and IFAR is the in-flight aspect ratio (defined as the target radius divided by the target thickness at a convergence ratio of 1.5) [2].

- Resistance to beam-mode (BM) growth, which is related to how evenly the laser heats the target. Stability to BM growth is constrained by using the initial value of Rb/Rt = 0.95, which provides good BM stability in OMEGA experiments. No data exist that demonstrate how changing the laser focus (called “zooming”) affects performance, so we must design targets with some yield redundancy to handle potential issues:

- lower-adiabat implosions have increased compressibility at the cost of greater RT growth

- lower-IFAR implosions (thicker shells) are less susceptible to fluid instability

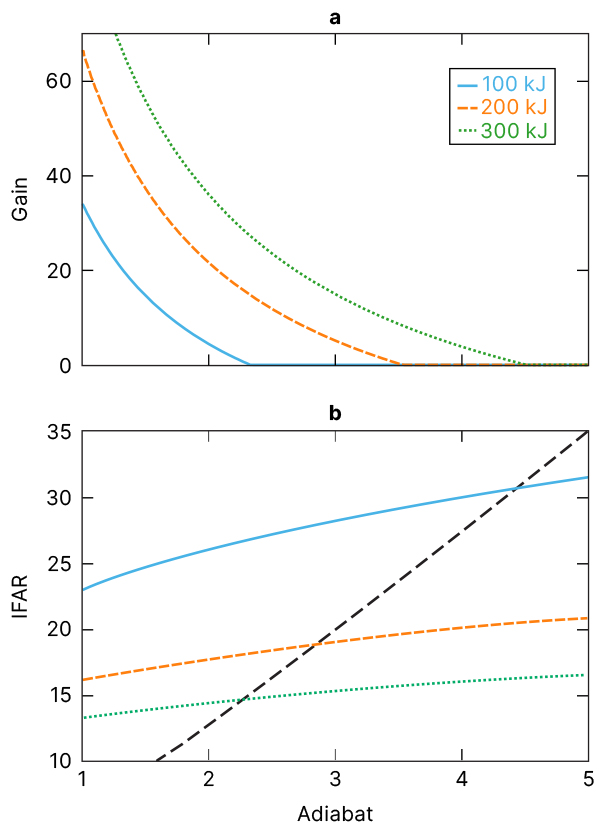

To find the best design, simple scaling relations are used to describe how the target’s performance and shape relate to factors like laser energy, pressure, and target compression. Minimum speeds are set for the imploding target to achieve fusion. Figure 2 shows the scaling relations for gain and IFAR as a function of adiabat at different laser-driver energies. The scaling relationships reveal that:

- 100-kJ laser designs are not sufficiently stable for fusion.

- 200-kJ designs are stable but only produce low energy output.

- 300-kJ designs are stable and produce good energy output.

The research concludes that 250 kJ of laser energy should provide a safe operating space. We can then refine the designs using 1D simulations and subsequently test stability with more-complex 3D simulations.

Surrogate Approach

This method is used to account for 3D effects within simpler 1D simulations by implementing a “surrogate model.’’ This model is based on a well-known simulation code (lilac) but includes additional calculations to estimate the impact of 3D instabilities. The surrogate model is trained using data from 3D simulations that were tuned to match experimental results. This approach allows researchers to account for the impact of zooming without limiting designs to a minimum implosion speed. Here, we used a genetic optimization algorithm with many simulations to find the best design.

There are many variations to this approach that differ in the form of the surrogate and how it is trained. Possible variations include: (1) modifying the outputs of simulations to match experiments using a transformation function such as a power law [1] or neural network [3]; (2) modifying the inputs of simulations to match experiments [4]; and (3) training a neural-network surrogate to match 2D/3D simulations that have been tuned to match experiments [5].

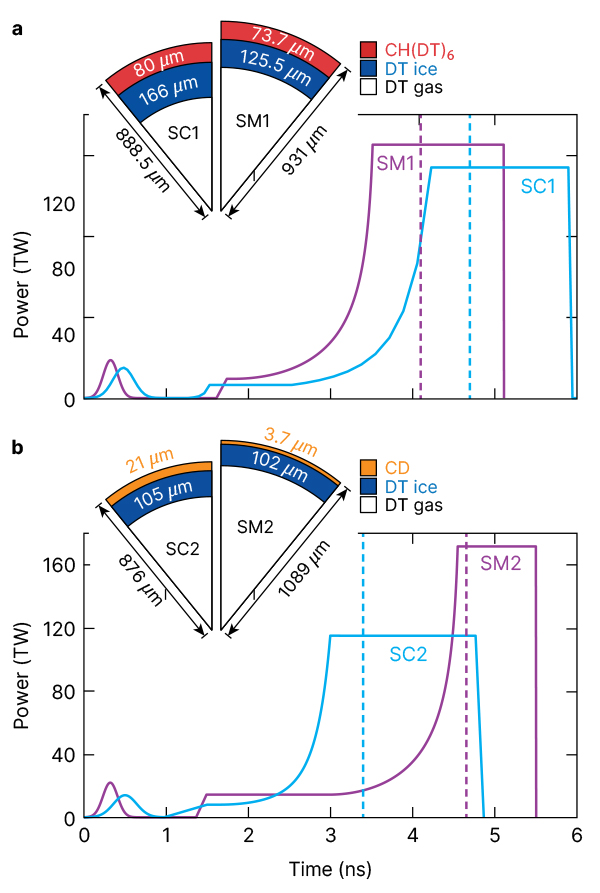

Implosion Designs

The 1D constraints used in both approaches include 250 kJ of laser energy, targets of deuterium–tritium (DT) gas-filled capsules with a DT ice layer and either a plastic foam wetted with liquid DT or deuterated plastic ablator, and pulse shapes consisting of a single picket followed by a foot and a smooth rise to constant peak power. Additionally, single-stage zooming was used (the size of the laser focal spot was reduced partway through the laser pulse). Finally, it is assumed that LPIs like cross-beam energy transfer have been mitigated through the use of laser bandwidth [6,7,8,9,10,11], but the laser intensity was limited to 1.2 × 1015 W/cm2 on the basis that higher intensities may require more bandwidth than is practical.

Each approach was used to design an implosion with a wetted-foam ablator [stability constraints and surrogate model (SC1, SM1)], and another with a plastic ablator (SC2, SM2). The various target designs and pulse shapes are shown in Fig. 3. In the SM approach, the designs were optimized using the levels of imprint and beam mispointing observed in OMEGA experiments. The SC approach generally leads to smaller, low-adiabat targets with smaller hot spots and larger shells. Conversely, the SM model favors designs with higher adiabats and high aspect ratios that efficiently couple energy to the hot spot without assembling large amounts of mass. Because the SM designs make a more efficient use of the laser energy, they do not need to be zoomed as strongly and therefore have small perturbations from beam modes and mispointing. A next-generation facility, however, could be designed to operate with smaller laser focal spots, which would make the SC designs more tenable. This would be possible through a more-symmetric arrangement of a higher number of laser beams and smoother beams.

One of the main advantages of using multiple design approaches is the ability to compare predictions. When multiple design approaches demonstrate that a design is stable, our confidence in the accuracy of the results increases. When approaches disagree, further investigation is warranted. Table I shows the design parameters that are needed to evaluate the stability characteristics of each design. Despite the lack of any explicit stability constraints enforced on the designs, the SM designs satisfy or nearly satisfy the stability constraints from the SC approach. SM1 is the only design, however, that simultaneously satisfies the stability constraints and is predicted to ignite (gain = 2.3) in the surrogate model.

Validation with 2D/3D Simulations

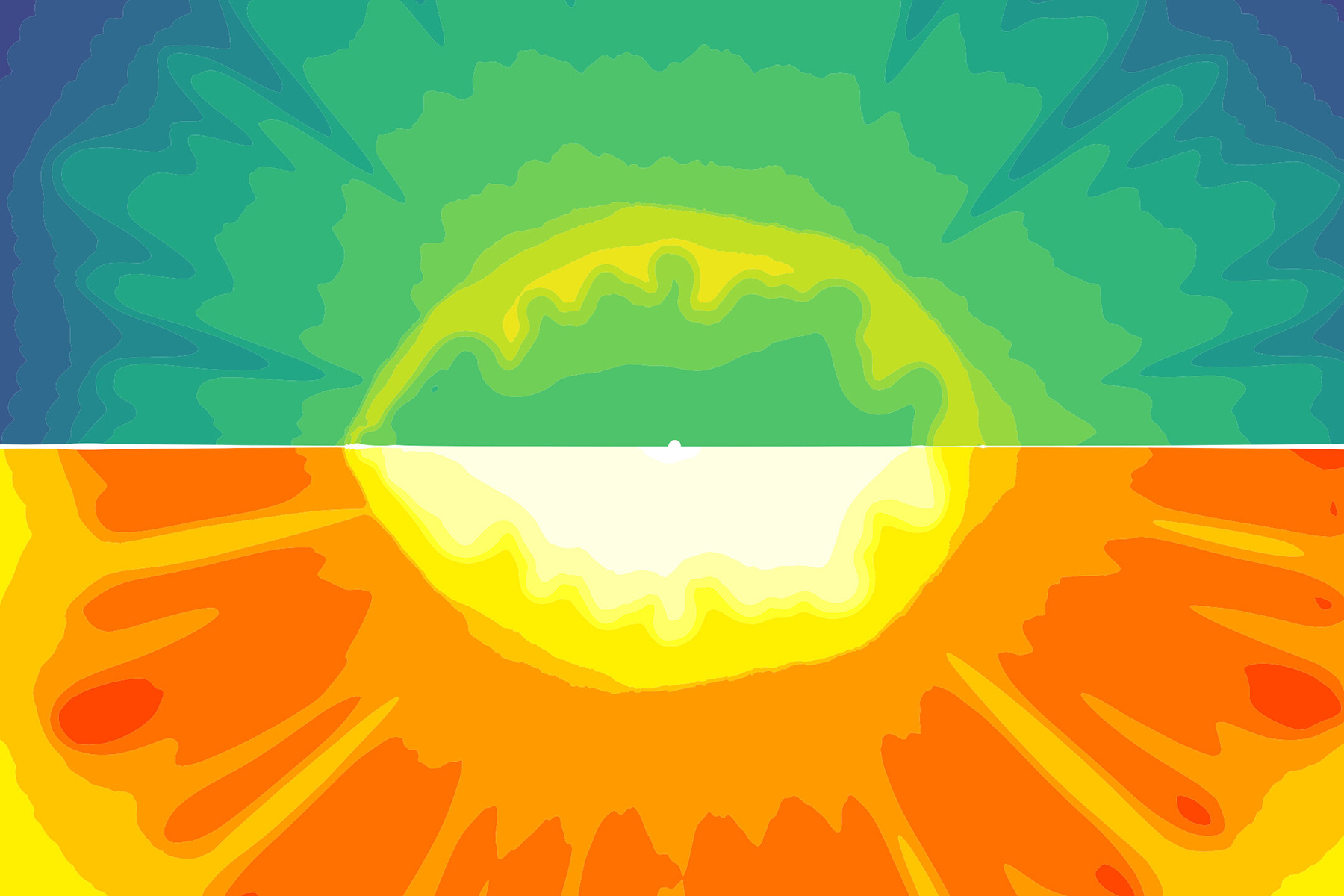

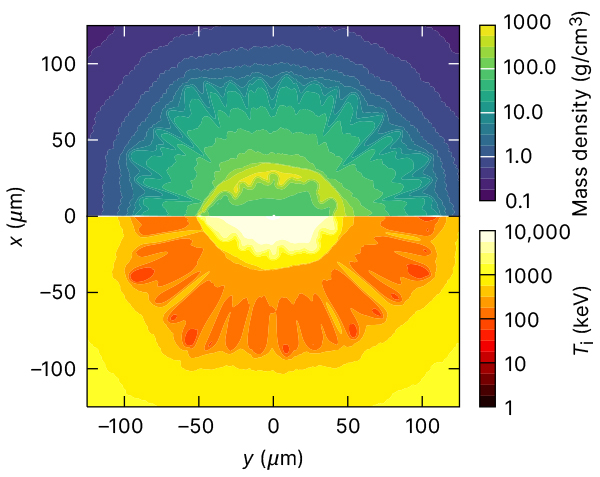

The design approaches discussed here are intended to accelerate the ICF design process by solving an optimization problem using 1D simulations that are informed by experimental measurements. Regardless of the approach used, an essential part of the process is to validate the predictions and verify the design stability using 2D/3D simulations. Although this still does not guarantee design performance, it provides an important additional data point when evaluating ICF targets and their robustness. Figure 4 shows the plasma conditions from 2D draco simulations of the SC1 design at bang time using nominal RT seed levels and no mispointing. The 2D simulations predict that increasing the number of beams around the target chamber from 60 to 108 increases symmetry to the point where gain > 1 is preserved.

Corresponding authors:

W. Trickey (wtri@lle.rochester.edu)

R. K. Follett (rfollett@lle.rochester.edu)